Kāne'ohe Bay, late 2019. I put my fins on, clear my snorkel, and slide off the side of the 17’ Boston Whaler. I dive down head-first, popping my ears as I go. In my hand are three cameras that I place on the reef, about 5 meters deep. A few colonies of Montipora rise from the sandy bottom, glowing a pale white. The GoPros will sit here for the next 20 minutes, watching the fish in the area. I look around once and think how murky this reef always seems. Then I make my way up. A few meters from the surface, my left ear makes a crackling sound, and I feel a second of piercing pain. When I get back on the boat everything is shaking and slanted. It’s raining over the water now. The sky is grey. The ocean twists and coils into the horizon.

A month later, the doctor tells me it is “very unlikely” that I will recover any hearing in my left ear.

I lie in bed for a week after that diagnosis, drugged on steroids. Audiogram – no change. I spend 3 hours every morning in a hyperbaric chamber for 10 straight days. I flip through a lot of The Surfers Journal, imagining myself on long, clean waves in some unknown corner of the world. I read The Overstory. Three more audiograms. My left ear fails the test each time. By December, the doctor says there’s not much else to do. The MRI and CT scans are fine. It was just an accident. Rare and unlucky, but an accident. “You’re young” he says. “You’d be surprised what your body can get used to.”

I think of the body of the coral that continues to bleach in the remnant heat of summer. How some colonies only die partially, dead cells surrounded by ones that continue to function. Sometimes, a coral dies, but leaves an imperceptible sliver of living tissue behind. Inside this bit of tissue thousands of algal cells are still harnessing sunlight. Just twenty or thirty corallites that continue to build skeleton. It’s funny that death and repair can occur so close to each other in this animal.

My body, on the other hand, feels like it is afraid of everything. Afraid of going to a bar (what if you can’t hear the conversation), afraid of listening to music (what will it sound like), afraid of talking to family (who only want to be with me). Most of all, it is suddenly very afraid of being in the water. I’m not sure how to deal with this because I am mid-PhD, and I have spent the better part of my life studying marine biology. And technically, I have been cleared to dive again. I constantly wonder if I have made this into a bigger deal than it actually is – it’s just one ear, after all. But that silver lining does nothing to comfort me.

So I learn, anew, about loss. Working in the field of conservation this past decade I think I am familiar with the feeling, but it hits you in a different place each time. This time I lean heavily into my friendships, the ones that go back to before I was even really me. The stability of those relationships - their unchangingness - is an anchor. The anchor allows me to drift. I drift into stories. Good old escapism – there’s a Buson haiku phase, a Barry Lopez phase, a memory palace phase. I comfort-read Invisible Cities for the hundredth time. I wander through parks with W.S Merwin poems. For two weeks I dog-sit two pups in a rainforest who don’t care about anything but their daily walks. I get really invested in a storytelling workshop and tell a very embarrassing story about doing science as a 22-year-old. The whole time, my left ear rings and trills and fills my brain with the sound of crickets. Thankfully, some people in the audience laugh at the right moments.

I think that maybe what I am calling loss is also vulnerability. Maybe there’s no real difference. And maybe we’ve all felt versions of it this year, as we lose, regain, lose again. Olivia Laing writes in Lonely City how ironic it is that loneliness, which by definition seems to isolate us from each other, is so universally experienced. For me, there is hope in that collective feeling, even if we must arrive at its resolution in our own individual ways. And even if that resolution slips back into muddy territory, forcing us to look at ourselves again, to be patient with what that might return.

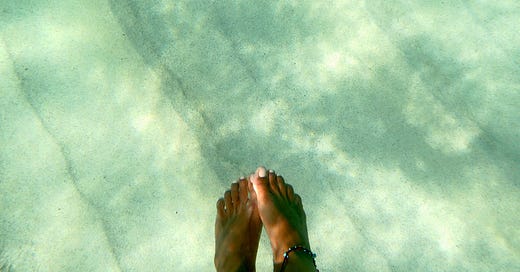

One evening in Rinbudhoo last year, I went for a swim off the southern beach and soon reached deeper reef. The light of sunset fell through the water in golden streamers, landing on fields of coral as far as the eye could see. Later, I learnt from a local resident that this reef had not existed five years ago and had only appeared when they had dredged a small channel nearby for boats to enter the lagoon. “Something changed after that, maybe the direction of the currents, but we started seeing a lot of baby coral here”, he said. Death and repair. They follow each other around.

Invisible Cities, an old favorite

Two great poems by W.S. Merwin:

https://merwinconservancy.org/2020/08/lunar-landscape-by-w-s-merwin/

www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/41947/to-the-light-of-september

That story about doing science as a 22-year-old was published as a podcast

Olivia Laing’s The Lonely City:

Hugs,

Shreya

You can find me on Instagram as @shreyodo

A few more things

To read:

The Trouble with Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature, William Cronon

To listen to:

Imaginary Advice, Ross Sutherland (the Moon)

Julia’s Trail, a playlist on Spotify. (I made this for my friend Julia last year, so weird pandemic melancholy meets pandemic hyperactivity)

To watch:

Torren Martyn doing beautiful things on waves

Zoe Todd on fish and Indigenous Law

A short film, Valen’s Reef

Another short film, Dances With Whales

This is beautiful! :)