This is my newsletter #16: Shruti Sunderraman

Hi, I’m Shruti, and I’m a writer, editor, and plant whisperer. I’m fairly tired of the intellect, and find comfort in soft edges. This newsletter will be a lot of the latter, and I think that is intelligent.

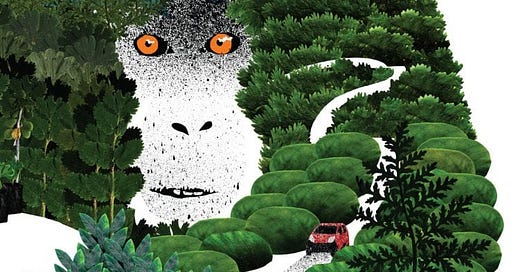

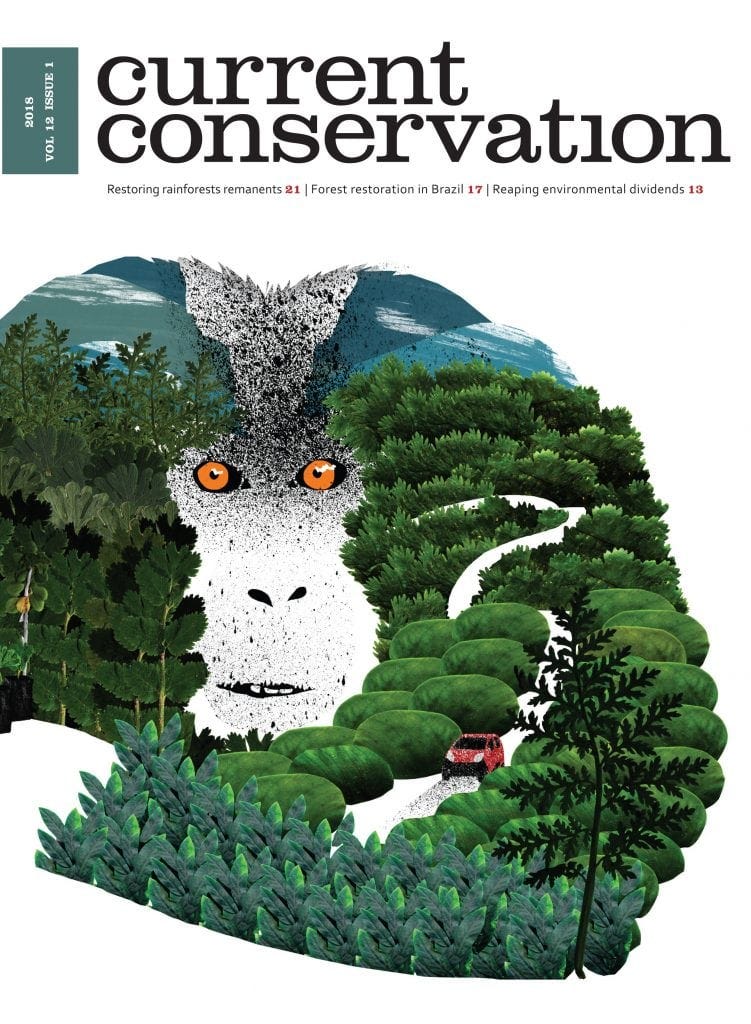

Life in conservation

As the Executive Editor of Current Conservation (our website is under renovation), I am constantly astounded at the stories I get to read about the natural world. To hoot my own magazine’s horn (I refuse to be ashamed), I would like you to introduce yourself to:

Zoya Tyabji’s world of studying dead sharks at Port Blair. It’s not the Jaws movie you expect. I think Jaws ruined a lot of sharks’ lives. No, you don’t need another boat, son. You need to leave them alone.

Amiya Hisham’s adventures with slugs and snails she finds in her Kerala home. They’re very paavam.

Korean housewives folding clothes: a mood

My YouTube algorithm is my most precious digital commodity. The Universe speaks to me through YouTube. Digital horror, but make it hippie. Lately, I have obsessed with Korean women cleaning their homes on YouTube. I call the world of Korean women cleaning, ‘interior lullaby’. For when these Korean entrepreneurs upload videos of organising veggies, growing impossibly neat balcony gardens, tucking their lived-in beige bedsheets in, I am soothed. The napkins are folded. The cat is fed. All is well.

my life is pretty –

cardsu –

A woman I am grateful for choosing to write: Vijeta Kumar

I am not quite sure when I started reading Vijeta. I found her before my The Ladies Finger days. Perhaps it was her story about Arundhati > Baahubali that won me over. Perhaps it was the one about her mother being afraid of Lorelai Gilmore. Perhaps I’ve been reading her from a different life. Vijeta is one of my favourite things about reading. I am simply grateful that she chose to write.

Follow her, contribute to her, and look forward to waking up another day.

www.rumlolarum.com

While you’re on Instagram

Now that we’re more online than we ever were before, here are some accounts I follow that add something more than unhelpful inhalation of dopamine.

Bright Side of Ig: It’s cliché, and it works. Just an account full of people doing nice things for each other. You know, to remember that still happens and stuff.

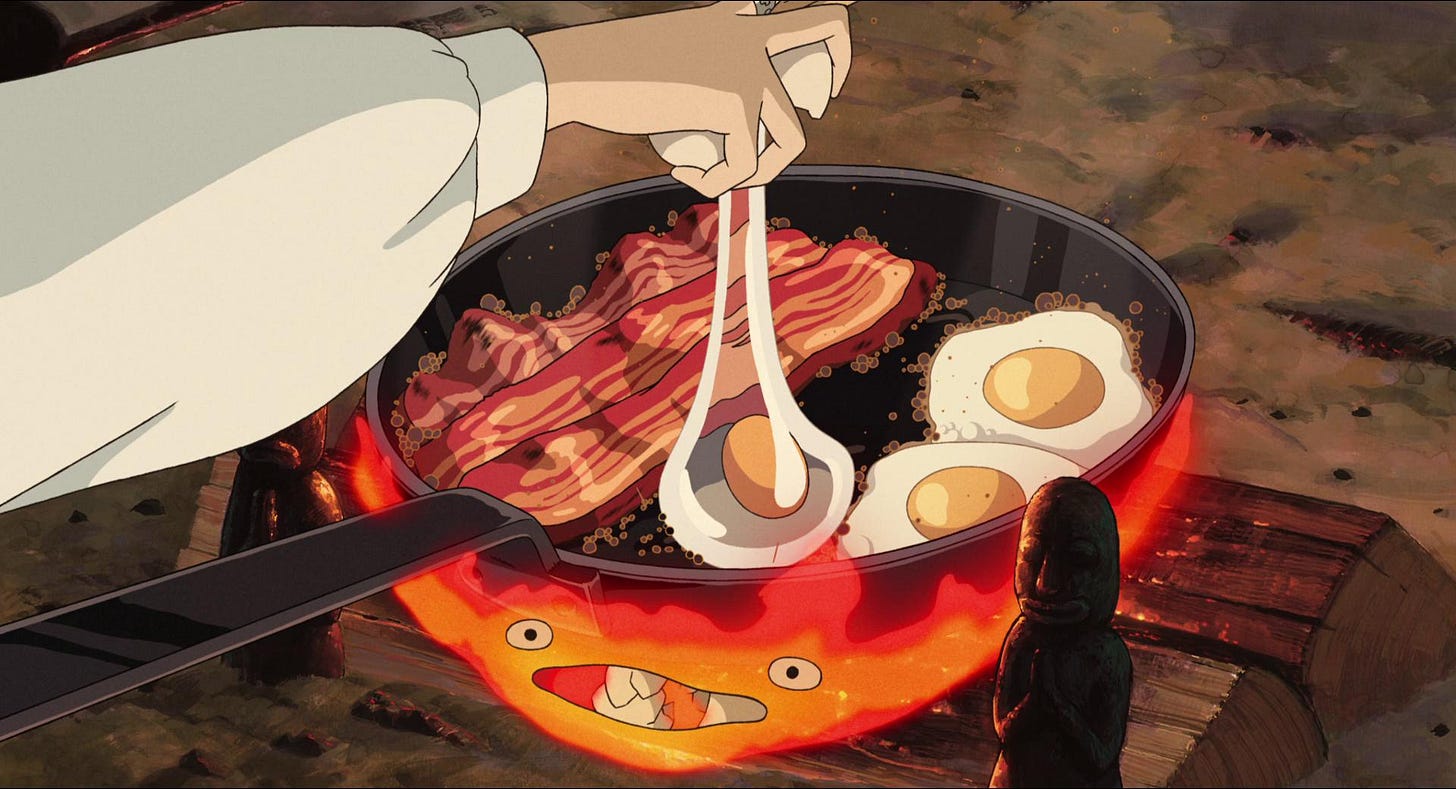

Ghiblifood: My favourite thing about Studio Ghibli movies is their impossibly enticing food. This account, thankfully, posts pictures of Ghibli food to save us all.

Curiocity Collective: An initiative that talks wonderfully about things that help you build a better relationship with yourself, and the place you live in.

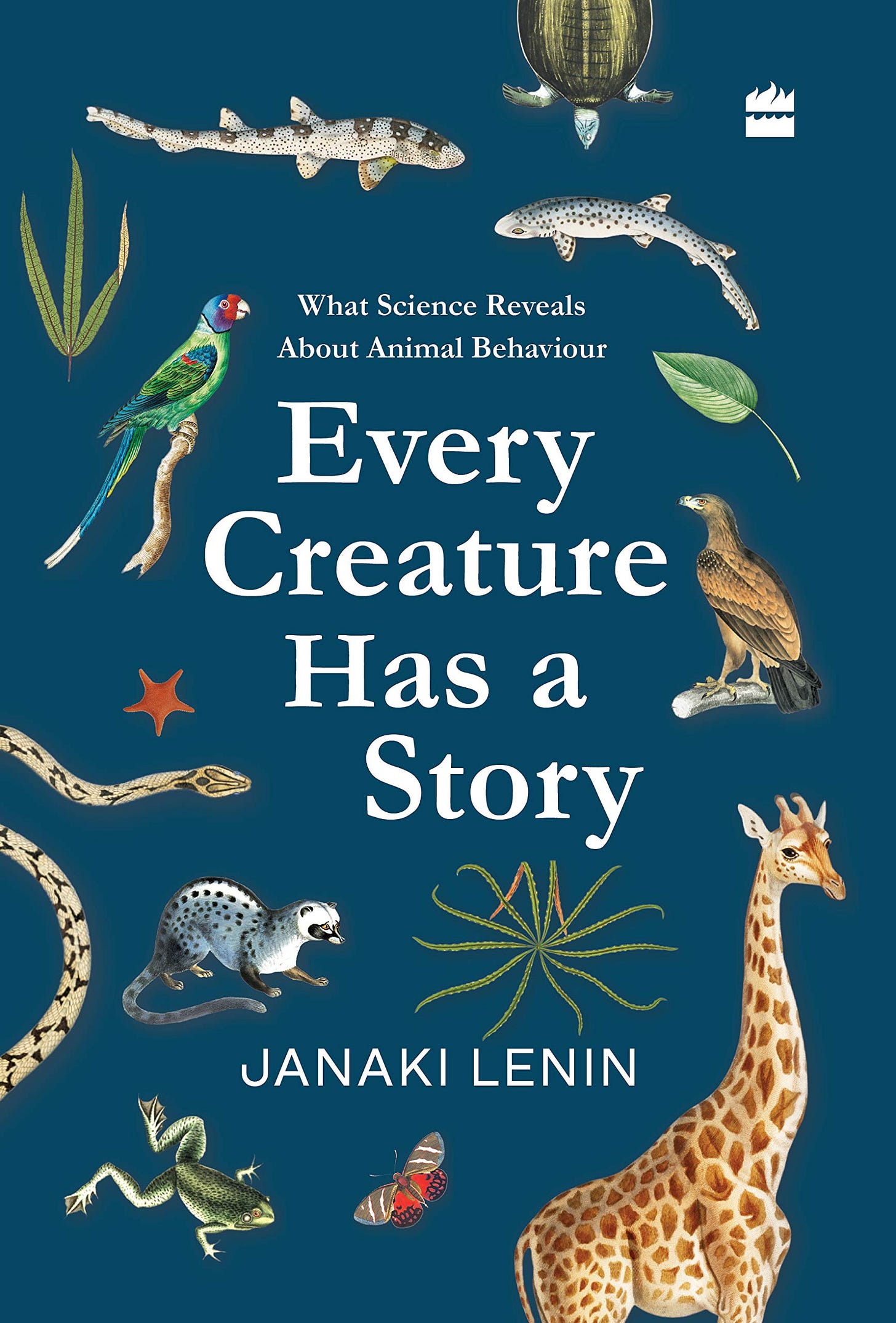

Read this book:

Every Creature Has a Story and other ways of living

When faced with confronting prejudice, one of the most common arguments we hear is “this is not natural” or “that’s just not how nature works” or “there’s nothing in nature that backs this”. These lines are usually used to justify prejudices we hold with topics like varying sexualities and genders, single parenting, socio-economic hierarchies, emotional intelligence and vulnerability, racial discrimination, non-ambitious living, anything that defies conventional life decisions that don’t conform to comfortable social boxes. I’ve always found this argument amusing. Despite spending many thousand years as bipedal creatures, we are still searching the heart of the wild, trying to understand its secrets and peculiarities. What we understand about natural behaviour is but years and years of documentation and curiosities. To use something so evolving and tenuous in an unexamined argument feels like a prelude to a laugh.

If working with conservationists from all over the world in the course of running Current Conservation has taught me anything, it is that one cannot assume anything about wild behaviour with absolutism. We can observe it, document it, even participate in it, but to be absolute in predicting natural behaviour feels counter-intuitive. Which is why, human absolutism while justifying prejudicial behaviour as “natural” makes no sense to me whatsoever.

The stories that the wild has to offer about natural behaviour are myriad and vast. And in so many instances, incredibly surprising. Take the story of the Pacific striped female octopus in Janaki Lenin’s latest book Every Creature Has a Story. Female octopuses have been documented to display hostile behaviour towards mates. In the world of cephalopods, it’s actually quite a dangerous game for male octopuses to latch onto a female and mate without being eaten. But the female Pacific striped octopus has other plans. Lenin describes how scientists were astounded to find amorous behaviour in the female Pacific striped octopus. In fact, the scientist who first noted this behaviour in 1975 was ridiculed by most of the scientific community for theorising something so impossible and “unnatural”. Sound familiar?

In 1975, Panamanian marine biologist Arcadio Rodaniche was surprised that larger Pacific striped octopus didn't copulate like other octopuses but more like squids and cuttlefish. He watched in amazement as matching pairs snuggled up together in the same den for a few days like honeymooners and had intimate sex by locking mouths and linking their sucker-lined arms. They even shared foot mouth-to-mouth like lovey-dovey humans, a suicidal move for males of other octopus’ species. The pale-coloured female enveloped her darker mate, and he responded by jetting ink. No other octopus behaved so sensuously. While female octopuses of other species died soon after laying eggs, larger Pacific striped octopus mothers survived for months afterwards.

Another story that stayed with me in the book is that of grieving chimpanzees in Chimfunshi Wildlife Orphanage Trust in Zambia. Generally, chimps don’t display grieving behaviour when a chimp in the community dies. The way Lenin talks about the perception of death in animals gave me pause for thought. As possibly the only species in the world that have conscious perception of the permanence and inevitability of death, it feels rather strange and lonely to be sitting with this knowledge. In chimpanzees, death usually doesn’t mean something as permanent as.. well, death. The others in the community usually leave the dead alone without perception of permanence. But Lenin enunciates through example of one community of chimpanzees in the zoo that actually mourned the death of one of them – Thomas – in a hushed gathering (very unlike chimps to be hush in a group). The way Lenin describes the collective psyche of the group (through observation, and cities studies) is heartbreaking.

Ignoring the caretakers' calls to feed, Violet, the dominant female, who had been watching and, stood up on her hand legs and screamed. She looked back and forth as she made her way towards the body. When she was close enough, she hit it hard before running away. Except for these dramatic interludes, most of the others gathered quietly around the body, while some inspected it. Van Leeuwen says sitting still is not typical chimpanzee behaviour. After Violet left, Noel, another adult female, approached the corpse and cleaned its teeth with a grass stem. Chimps examine and clean each other's teeth. But this is the first report of one cleaning the teeth of a dead one and using a tool for it. She then stuck the stem into her own mouth. Noel wasn't interested in what he had eaten since she ignored the keepers' call to feed. Picking Thomas's teeth seemed to be meaningful to her, says van Leeuwen.

Lenin has spent a significant amount of time writing stories from the wild, working with researchers, writers, scientists, and conservationists over the years. Her repertoire of gathering stories is quite extensive. The collection of essays in Every Creature Has a Story is reflective of her scientific interest and child-like curiosity in learning everything within reach about peculiar behaviours of creatures who are, in many ways, expected to behave otherwise.

One notable aspect about Every Creature Has a Story is that every story told about each creature is left with an open-mindedness that the premise of the observed behaviour began with. Essentially, even while describing how scientists came to conclude a particular behaviour, Lenin leaves room for questioning it. Much like the wild, Lenin’s writing and questioning leaves room for waves of transformation.

Apart from the mourning chimpanzees and the amorous octopus, the book covers behavioural stories from many animals, birds, insects, reptiles, and parasites in the wild. There is also a lot of room for laughter in the book. For example, the dragonfly observed in Switzerland that just wanted to be left alone. This particular dragonfly feigned death to avoid sex. Even in the throes of fascination with this story, it’s impossible to not get a few laughs out of this particular dragonfly. Story of every exhausted working woman’s life.

About 60 percent of the observed female hawkers evaded their suitors, leading Khelifa to think this is a common behaviour in the species. When they crash-landed, they didn’t suffer concussions or lose consciousness. They were alert even as they viewed the world upside down, and the researcher could catch only for while twenty-seven escaped. To them, sex-obsessed males were no different from hungry predators.

Amen, sister.

If we dive into the stories of the octopus, the giraffes, the grieving chimps, the emus, and the altruistic whales Lenin talks about in Every Creature Has a Story, we learn how no two things are always the same. This is as much the case in the concrete jungles we build around ourselves as it is in the wild. Perhaps you won’t walk away from this book with this parable of prejudice. Perhaps you will just ride the wave and laugh along with the playful keas in New Zealand that Lenin delights in regaling us about. And there’s so much virtue in that.

To me as an editor and (and I’d like to think) a friend of conservation, this book helps me think about the clinicality of my work and helps me ask if observations, ways of living backed by analogies and studies need to necessarily be boxed. The idea of narrating the very real lives of these creatures with stories is a particularly simple and powerful move made by Lenin in Every Creature Has a Story.

In a world surrounded by increasingly complex questions, it begs the question – who are we without stories?

You can place an order for her book here: https://champaca.in/products/every-creature-has-a-story